This Sunday we begin the season of Advent, and in the readings we will hear St. Paul telling us, “It is time for you to wake up from your slumber” (Rom 13:11), and Jesus reiterating the same message: “Stay awake!” (Mt 24:42).

With these two similar calls, we enter fully into the spirit of Advent. It is a time, then, to awaken, to be attentive, to scan the horizon and perceive in it the signs of God’s presence, which is coming and will be born to us at Christmas. Advent is also a time to identify the breaches that Jesus mentions in the same passage: cracks through which our good intentions, our desire to be good people and to live according to the Gospel, can slip away.

In these times, in which we live immersed in the digital revolution, perhaps an analogy with technology can help to illustrate what this season of Advent is all about. We know that every now and then we must restart a computer or a phone. We reset them or reboot them. Sometimes we humans also need a reset, and Advent gives us the opportunity to do so.

We restart our computers because something isn’t working properly: some harmful habit persists in the system, an error that has remained, causing problems, and that needs to be fixed. And we also restart our computers to access updates that are now available and that, once installed, will allow everything to work better.

To restart a computer, you have to turn it off. The same goes for us. Every now and then, we need to «shut down the system» in the sense of silencing the many noises that deafen us, that come from all sides and prevent us from thinking clearly. There is a lot of noise in politics, on social media, in television talk shows, and there is also noise that arises from within us in the form of old grudges and open wounds that we haven’t been able to heal. All this noise leads us to accumulate tensions, anxiety, resentments, bewilderment, and anguish.

In Advent, let’s begin by turning off the noise. One of the main characters of this season is John the Baptist, who went to the desert: that is, he distanced himself from the noise. From John, we can learn his choice to refuse to live amidst a whirlwind of activity, constantly absorbing information and noise, without time to process it. In the desert, John will offer a clear and new message because he has known how to distance himself from the noise—to then be able to think, and to understand what God wants from him.

And so, in Advent, after switching off the system, let’s restart it —with a different attitude. We can identify what was wrong within us before: what unhealthy habits were bothering us. Perhaps we had entered a cycle of negativity and pessimism. Perhaps we had started drinking too much or wasting time with other activities that brought us nothing positive. Perhaps we had begun to fuel a conflict with someone, to cultivate hatred, resentment, that kept growing. In Advent, we restart the system, our lives, from scratch, without those harmful habits.

And, in Advent, as we restart—as we awaken—we also seek new updates: we prepare to look at others with fresh eyes, to begin healthier habits. We watch for resources available to us, that until now we had not been using: people we should listen to a little more, readings that could enlighten us, acts of solidarity with the poor, which will strengthen our faith. Advent can be all of this: a true reset of the heart.

In this coming Sunday’s Gospel reading (21st Sunday in Ordinary Time, Cycle C), we will hear that Jesus, responding to the question of whether only a few are saved, says the following: «Try to come in through the narrow door. Many, I tell you, will try to enter and be unable» (Luke 13:24).

At first, this sentence may seem like bad news to us. Couldn’t God have designed a much wider gate, one through which we could all pass easily? Indeed, don’t we tire of preaching that God is pure hospitality, that precisely one of the emphases of Jesus’ message was the mercy of the Father, who opens his arms wide to the whole world? How can we reconcile this idea with the image of the narrow door?

It seems to me that here Jesus is underscoring something fundamental, something we should never forget. That the spiritual life requires effort. Is the Gospel good news, and a path to fulfillment and happiness? Absolutely. Does it require sacrifice, deep inner work, and a firm will to overcome our most selfish tendencies and our pride? Yes, that is also true.

The path that Jesus offers is not a playful walk on the beach. It demands discipline and a patient work of self-knowledge, to discover within ourselves both what hinders us (which must be abandoned) and the living presence of the Spirit in the depths of our hearts (which must be welcomed and strengthened). It is a journey of transformation… that everyone can do (this is the good news!) —and that is why Jesus also affirms that all kinds of people, from the East, the West, the North, and the South, will sit at the table in the Kingdom, but that no one is exempt from walking.

I like to think that the narrow door is, in fact, a gift. Because those who arrive at its threshold with a swollen ego cannot cross it; or with suitcases packed to the brim with petulance, or resentment, or vanity, or a desire for prominence, or a lust for power. We must abandon all of that so that, light, simple, and at peace with the exact dimension of our goodness, our achievements, and our failures, we can then happily cross over to the other side. The narrow door is a gift because it reminds us of so many useless things that we carry around with us —things we tend to defend with passion, and yet they serve no purpose. Or they serve no purpose for the only thing that really matters: sitting down to enjoy the banquet in the kingdom.

Happy Easter!

After having experienced the celebrations of Holy Thursday and Good Friday, with their various liturgical expressions (the washing of the feet, the Stations of the Cross, the adoration of the cross) and having accompanied Jesus through the reading of the Gospel stories, finally yesterday, Saturday, after sunset we celebrated the victory of life over death: the stone was rolled away, and the tomb was empty! «Why do you look for the one who lives among the dead? He is not here. He has risen!»

With the Resurrection, at dawn on Sunday, we reached the center of our faith, the joyful celebration that history did not end in the dark dampness of a hopeless tomb.

At the Easter Vigil, so rich liturgically, we use three fundamental signs to speak of Jesus’ resurrection: first, fire; then, water; and finally, the bread and wine with which we celebrate the Eucharist.

There is an implicit invitation in the use of these signs: the invitation to be fire, water, and broken bread for others.

At times we walk in the dark, in the midst of very cold nights: the icy, shadowy night of loneliness, discouragement, hopelessness, fear, and the prison in which our selfishness imprisons us.

Today we are invited to be fire: a fire that brightens the world and a fire that warms it up. A fire that lights the way and disperses the shadows, a fire that comforts us and restores life when our bodies and souls have already grown numb, anaesthetized by the cold.

At times we are a parched, cracked, sterile land, a desert where nothing grows, a barren wasteland where others cannot find even a green breeze of joy.

Today we are invited to be water. Fresh water that renews and cleanses, that gives life, that with its fruitful course transforms deserts into gardens.

At times we are hungry. We feel weak, lacking every kind of nourishment: we lack bread, strong friendships, purpose, hope.

Today we are invited to be bread and wine for others: to nourish those who are spiritually anemic with our solidarity and our affection, also to seek nourishment in the witness and example of others, and in Jesus of Nazareth, conqueror of death.

Let us celebrate Easter: let us be fire, water, and food for our brothers and sisters!

Lent, this special season that prepares us for Holy Week, is a season that, among other things, has a penitential component. It is good, from time to time, to review our lives, our attitudes, and the way we treat others, and to do so with a sense of repentance. Where am I allowing myself to be led by selfishness and indifference? Have I hurt the people around me? Am I wasting time and energies in activities that don’t help to build the Kingdom?

We should not live immersed in an unhealthy sense of guilt, but there’s nothing wrong with looking in the mirror from time to time, with absolute sincerity, asking ourselves how we could improve aspects of our daily lives that are not entirely in tune with the Gospel, or that contradict it.

Jesus did not come to overwhelm us with the weight of our sin: in fact, the Gospels make it very clear that he came to free us, among other things, from feeling guilty about everything, assuring us that no matter how many mistakes we make, we can always count on the Father’s mercy. And yet, it is also true that on many occasions Jesus spoke harshly about those who, believing themselves to be perfect and holy, were incapable of self-criticism and did not accept the need to reorient their lives toward God.

On one occasion, looking with sorrow at his contemporaries, he said, «this generation is perverse. It asks for a sign, and none will be given it except the sign of Jonah» (Luke 11:29). In fact, we read this text on Wednesday of the first week of Lent. The interesting thing about this sentence is that Jonah, when he went to preach the conversion of Nineveh did not perform any sign! Indeed, before the Ninevites, Jonah did not do any miracle. The biblical text tells us that when he finally arrived at the great city (after trying to escape the mission God had entrusted to him), he simply «walked for a whole day, proclaiming, 'In forty days, Nineveh will be destroyed!'». That’s all. He didn’t back up his preaching with any flashy gestures, nor did he accompany his words with any demonstration of power, showing that Yahweh was on their side. He simply announced that God’s patience was running out... and that was enough for the Ninevites to make a resolution to change their ways and convert.

No sign will be given to us, either, other than the (non)sign of Jonah. Therefore, we should not wait for some spectacular and incontestable event to happen in our lives in order to change those attitudes that distance us from God. The great sign we need to reorient our lives toward goodness has already been given to us: the preaching of Jesus, the message conveyed to us by the Gospels. What more can we hope for, what could be more definitive than the words of the Messiah?

We can all sometimes fall into the self-deception of telling ourselves that we are waiting for something prodigious to happen, a miraculous sign, a truly singular event, to initiate the processes of change that are essential in our lives. «I will change,» we tell ourselves, «when» —and we condition our conversion on the occurrence of great wonders around us. In reality, waiting for astonishing miracles to occur so that we can begin to correct our mistakes is a form of immobility. This Lent, we would do well to remember that we will be given no sign other than the sign of Jonah: the sign of a man announcing that there are better ways to live, with no other power than the reason and force of his words.

One of the “mottos” of Advent, one of the phrases that captures the spirit of this time that we began last Sunday, is “Come, Lord Jesus,” taken from the end of the Book of Revelation (Rev 22:20). It is, we could say, one of the most appropriate prayers of Advent.

And yet, it is important to make sure that we understand these words correctly. Because they are not a request, nor a demand that we address to Jesus so that he decides to come to us, as if he, for some reason, was hesitant and we had to convince him to actually come to the world.

“Come, Lord Jesus” is a request addressed to ourselves: a prayer in which we ask to gather the wisdom and the strength to open the doors of our lives to him and remove all the obstacles that we sometimes put in the way, blocking his way. Obstacles that we put because, in reality, we are afraid of his coming.

And why, we should ask ourselves, are we afraid of Jesus? Why do we resist Jesus' coming (even if we keep repeating "Come, come...")?

One possible answer is that we know, or we sense, that in one way or another Jesus always comes to unsettle us. He comes to give us a little push, to urge us to go further in our generosity, to abandon the routines that numb our conscience, and to make an exodus, outside the comfort that binds us and the territories that we already know, towards the risky life of the Gospel. That is why deep down, perhaps unconsciously, we fear Jesus' coming.

It would be good to identify the attitudes that tend to tie us into a desperate search for comfort. Review them, understand that they impoverish us and reject them. Then we will be able to say with all sincerity and vigor, in this Advent and always: "COME, LORD JESUS!"

29/08/2024 -

SALOME

Today, August 29, the Church remembers the martyrdom of John the Baptist. I have always thought that the story that Mark tells us in the sixth chapter of his Gospel (Mk 6:17-29) functions as a parenthesis within the general narrative to describe the worst aspects of the world in which Jesus wants to announce his good news. In the scene, full of details, there is betrayal, hatred, violence, manipulation, vanity, cowardice. In other words, everything that stands against the hopeful message of the prophet of Nazareth. The terrible death of the Baptist is like a warning: Beware! The evangelist tells us: this is the landscape facing Jesus... and all of us.

The most disturbing character in the story is the young dancer—the girl who, without intending to, finds herself at the center of the action. Mark does not name her (he simply presents her as "the daughter of Herodias"). It is Flavius Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, who tells us that the little girl was called Salome (book XVIII, chapter 5,4).

Salome is disturbing because she is innocent and yet becomes the necessary instrument to bring about John's death.

Herodias, her mother, appears as someone without scruples, full of hatred and evil intentions, who from the beginning wants to eliminate the Baptist. She is, so to speak, "the villain," a character without nuances, almost a caricature. Her daughter, on the other hand, is a young woman without bad intentions who simply obeys what she is told: to dance for the king. And, once she has danced and Herod, dazzled, has promised her that he will give her whatever she asks for ("even if it is half my kingdom," he swears foolishly), she runs to ask Herodias what she should ask for. When her mother tells her to ask for John's head, the girl, without thinking twice, instead of refusing to participate in the tragedy, returns to the king and asks for the prophet's life.

None of us are Herodias, but we can all become Salome. That is the reason for the uneasiness that this young character should cause us. We are not perverse like the mother, but we can all, at times, be naive and frivolous like the daughter. Then we could allow ourselves to be manipulated by dark forces that overwhelm us and we could end up being instruments that favor the cause of evil.

Salome is a warning: she cautions us against the danger of falling into superficiality, of sinning by being naive.

The point, of course, is not that we should become distrustful of everyone in an unhealthy manner. The point is that we should never fall into naiveté. When we ignore the power of the hatred that dwells in some people, then it is possible that this hatred may end up taking advantage of our blindness.

We must avoid being like Herodias, but that is not the difficult part. What is truly hard is never to be like Salome either.

The ancient city of Philippi, today

During the Easter season—which we will conclude this coming Sunday with the great feast of Pentecost—, at Mass we have been reading the book of the Acts of the Apostles. Every year, when we engage in this exercise of reading continuously the second volume of Luke’s story, one is amazed at the depth, the narrative richness, and the wisdom of this account. Today I would simply like to focus on a scene that we find in chapter 16: the conversion of the Philippian jailer.

Let us remember the episode: Paul and Silas are in northern Greece, in the city of Philippi, «the main Roman colony in the district of Macedonia» (16:12). There, Paul expels an evil spirit from a slave who, with her talents for fortune-telling, until that moment had brought great profits to her masters. These, «seeing that all hope of earning money was gone» (16:19), accuse Paul and Silas of altering the city’s peace. Consequently, the magistrates order that the two Hebrews be flogged. After receiving many lashes, they are sent to prison. The jailer is asked to keep a close eye on them.

At night, an earthquake shakes the foundations of the prison, opening up its doors. The jailer, assuming that the prisoners have used the opportunity to escape, is about to commit suicide when Paul, from his cell, warns him that no one has escaped. The man, stupefied, throws himself at the feet of Paul and Silas and asks them how he can be saved. Then they proclaim the Gospel to him. Immediately afterwards—and this is what we wanted to underline—, the jailer takes them with him, washes their wounds and is baptized along with his family (16:33). Before being baptized, he cleans the wounds of Paul and Silas. These are the same wounds they had when they entered the prison, the result of the beating they received before being entrusted to the jailer. These are the wounds he completely ignored when hours before he hastily locked them up. Those wounds to which he did not give the slightest importance then, now touch him. Even more: now they are an emergency. The priority is to wash the wounds; then he can be baptized.

The way the jailer looks at Paul and Silas’ wounds is important. What was invisible before his change of heart—the bruises, the open flesh, the blood—later becomes essential. Perhaps this good man (dedicated to a profession as hard and dehumanizing as that of locking up criminals), draws with his own process an itinerary in which we can all see ourselves reflected. It is also an itinerary that establishes an infallible criterion to evaluate our degree of understanding of the Gospel. Probably, all of us can recognize ourselves in the jailer when we think of those times when other people’s wounds seemed invisible. All of us can think of instances in which God manifested himself to us precisely through wounded people. And perhaps we can remember with joy those moments when the wounds of others moved us, and we wanted to do something to heal them.

In the jailer’s journey we discover the fundamental criterion that distinguishes a person who lives the Gospel from a person who does not: the second is indifferent to the wounds of others. The first, on the other hand, does everything he can to alleviate the pain of those who suffer. The converted jailer, eager to follow Jesus, does not fall on his knees, overcome with piety, and praise God with half-closed eyes, nor does he run to the temple to offer a sacrifice, nor does he lose himself in complicated theological sermons: he rolls up his sleeves and cleans the wounds of his brothers.

The extent to which the wounds of others move us or not will always indicate, with surprising precision, the quality of our faith.

Isaiah is somehow the prophet of Advent. His texts (which, despite having been written twenty-eight centuries ago, can move us as if they had been composed yesterday) are especially present in the Eucharists of this time of preparation for Christmas. It is quite logical: as we prepare to celebrate the birth of the Prince of Peace in Bethlehem, we read the poet of Israel who most ardently dreamed about peace. Some of his most immortal and well-known pages are, in fact, beautiful songs against war and in favor of non-violence: «They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more» (Is 2:4)1. Or this passage, justly famous, which does not cease to amaze us in spite of being so well known: «The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them. The cow will feed with the bear, their young will lie down together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox. The infant will play near the cobra’s den, and the young child will put its hand into the viper’s nest. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, for the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.» (Is 11:6-9).

In this Advent of 2023, Isaiah's dream of peace seems very distant, even more distant and unattainable than a few years ago. The world, according to analysts, is becoming a more violent place, if we compare it with the scenario we had just at the beginning of the century. Apart from dozens of minor struggles (which, even though they are minor, cause countless victims), there are large-scale armed conflicts in Burkina Faso, in Somalia, in Sudan, in Yemen, in Myanmar, in Nigeria and in Syria... apart , obviously, of the war in Ukraine, in the heart of Europe (which will be two years old in February 2024, with hundreds of thousands of soldiers and more than 10,000 civilians killed to date) and the war between Israel and Hamas, which already accumulates nearly 20,000 fatalities. The Gaza Strip, paradoxically, is located less than sixty miles from Bethlehem, the birthplace of the Prince of Peace.

What to do, given this scenario? Should we forget forever about Isaiah and his dreams? Shall we surrender to the conviction that humanity will never be able to eradicate war? Must we understand that, as long as there are immense economic interests related to the arms industry, plows will never be forged from swords? It is a tempting position. The facts seem to support it.

The alternative is, of course, to argue that Isaiah's pacifist dream is a better path. To affirm that, in the face of the current return to war that we are experiencing, Isaiah, as well as the Gospel of Jesus (who will affirm that those who work for peace are blessed) are more necessary than ever. The alternative is to work so that these wars, today, are the last expressions of an ancient humanity, which one day will disappear, to give way to a new humanity, attached to peace, faithful to the visions of Isaiah and Jesus.

Each of us, with our daily attitudes —opting for non-violent ways to resolve the small conflicts in which we find ourselves, betting on dialogue and promoting justice— can work so that this new humanity is not an illusion. In Advent, in this Advent, it would not be a bad idea to redouble our commitment to peace. In the end, let us not doubt it, Isaiah will be right.

(1) This phrase, as is well known, is carved on a wall at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

These last two weekends, as we celebrated the 21st and 22nd Sunday in Ordinary Time (cycle A) we have read the account of Jesus’ dialogue with his disciples in the region of Caesarea Philippi, according to the Gospel of Matthew (Mt 16:13-27). At two different moments in the passage, Jesus addresses Peter with two contrasting phrases, using two statements in which the second seems to be exactly the opposite of the first. When Peter declares that Jesus is the Messiah and the Son of the living God, Jesus exclaims: «Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for no man has revealed this to you, but my heavenly Father» (16:17). Then, when Peter rebukes Jesus, telling him that it is impossible for him to be executed, Jesus, after speaking to him with unusual harshness (treating him as Satan!), adds: «You think like men do, not like God does» (16: 23). First, he said that Peter’s declaration of faith came from God, then Jesus states that Peter’s attempt to divert him from his mission is a purely human thought. The story, in summary, makes it very clear that there is a way of thinking proper to men, which is opposed to God’s way of thinking.

How do «men» think? How does God think? What is the specific nature of each way of thinking?

We can deduce the answer to these questions from the context in which the phrases are pronounced, and also by looking at what Jesus says next: «Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it» (16:25).

To think like men—to think humanly, without taking the Gospel into account—is to put our well-being and our personal comfort before any other consideration. It is to place our peace of mind before anything else. It is to live avoiding conflicts, making sure that the anguish and suffering of others do not touch us; it is to live dodging problems, dangers and headaches. It is to make of our personal security the absolute good to which we aspire.

To think like God is to understand that sometimes we must risk our well-being so that the world looks a little bit more like the kingdom of God. It is to understand that, although our peace of mind is important, there are much more important things in life: the construction of a more just world, the creation of environments of authentic freedom, of spaces where everyone fits, where there is no room for exploitation and where no one abuses anyone: the reasons, ultimately, why Jesus (who thought like God, not like men) decided to go to Jerusalem to face the unjust system that oppressed his people, even though he knew that failure and death were waiting for him there.

We can go a little deeper: to think like men is also to see the world as something finished, completed, that exists to satisfy our needs. It is to conceive the world as a sort of a huge supermarket, with the shelves full of products and resources well arranged, ready for us to take them home... without thinking that, sooner or later, the supermarket will be empty.

To think like God is to understand that the world is a work in process, something we must help create every day. It is to imagine the world as a field that must be cultivated with skill, love and dedication, an immense garden that you and I can continue to sow, water, and prune, so that it never stops producing fruit.

To think like men is to see others as means to our ends, and to think: «From him I can get affection; from her, instead, money, since she is rich; from that one, advice, because he is wise; from the one a recommendation, since she is very well connected with important people»…

And to think like God is to ask myself: «What can I do for others, so that everyone I know may live better, fuller lives?».

In short, to think like men is to have a predatory mentality; to think that reality exists solely so that I may obtain from it what I need. Thinking like God is acting out of a creative mentality: what can I do to enrich the reality that surrounds me?

When we make decisions, whether they are trivial or critical, and especially if they are critical, do we decide thinking like the Peter who assured Jesus that he was the Son of God—or like the Peter who was frightened by the prospect of the cross? How do we live our lives? Thinking like God, or thinking like men?

We continue with our commentary on the Beatitudes of the Gospel of Matthew, which we started a few weeks ago. Today we take a look at the second one, which continues to stress the paradoxical nature of Jesus’ path to happiness.

Statue of Fray Antonio de Montesinos in Santo Domingo: he was

someone who allowed himself to be moved by the suffering of his brothers and sisters.

«Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted» (Mt 5:4)

How should we understand this statement, which apparently is an absolute contradiction? How can suffering have the key to the door of happiness? How can the afflicted or those who cry be happy?

Here, too, it is necessary to begin by clarifying that it would be very possible to conduct an erroneous reading of the beatitude, according to which Jesus would be glorifying and praising suffering by itself. Someone could, indeed, use this verse to affirm that anguish and sorrow are good in themselves, and that, therefore, Christians must desire and proactively seek their torments. And it is not so: Jesus dedicated his life to alleviate the pain of others, curing the sick, feeding the hungry, restoring sight to the blind, and denouncing those who, with their selfishness, made the weakest suffer... Christianity is not a masochistic religion.

A second thing that Jesus is not saying in this beatitude is that it is necessary to suffer here, on this Earth, in order to be consoled in the afterlife. This does not agree with the spirit and the thinking of Jesus. To say something like, «look, you must agonize in this world, because then you will receive comfort in Heaven» would imply the image of a cruel God, who first needs to see our tears to then open the door to those who will have won their place in Heaven by enduring hardships. It cannot be so, when, first, Jesus never despised this present world (on the contrary, he affirmed that «the reign of God is already in your midst», in Lk 17:21) and, secondly, he said that his merciful Father is always eager to welcome us, to open wide the doors of his house, where there is room for everyone (Jn 14:2): Heaven is not «earned» on the basis of our many tribulations.

How are we, then, to understand this second beatitude? Perhaps in the sense that in this life only those who are not indifferent will be truly happy. That is, those who toil so that their hearts do not harden; those who keep alive their ability to be moved by someone else’s pain.

Certainly, if your heart is made of stone, you do not suffer, nor do you ever cry. But your life is, then, inhuman, and empty. It is much better to experience sorrow and to mourn because you have a human heart—which is moved by the pain of your brothers and sisters―than to live protected by an armor of indifference that, yes, prevents you from suffering, but also stops you from feeling love.

Those who mourn are those who walk around the world without an armor, with empathy towards their neighbors. In the end, this ability to cry with those who cry will give us the certainty—and the comfort— to know that we did not waste our lives, and this will surely bring joy into our hearts.

In this second beatitude Jesus warns us against apathy. This warning is more necessary than ever, because today, overwhelmed as we are by a constant flood of news, which is often very tragic, it would be easy to fall into insensitivity. We read or hear that a jealous husband killed his wife, that once again a group of immigrants died in the desert trying to cross the border, that there have been more innocent deaths in the Ukraine, in Yemen or in the Congo, that Haiti has been devastated by another storm, that in Iran they have executed someone who cried for freedom or that in Uganda someone has been imprisoned simply because he is gay—and we shrug our shoulders, without giving much importance to what we have just read or heard, and we quietly continue to sip our morning coffee, thinking already about something else. That is an unhappy life.

In the priceless parable of the good Samaritan (Lk 10:25-37) we discover two conflicting urgencies. Indeed, the encounter with the wounded man on the side of the road confronts each of the three characters who go down from Jerusalem to Jericho with a dilemma: what is more important? My urgency to reach my destination as soon as possible, or the one of the stranger who bleeds to death before my eyes? The first two men, the priest and the Levite, decide —quite cynically— that their urgency is, so to speak, more urgent than that of wounded man. The Samaritan understands that no matter how rushed he is, or how important it is for him to get where he is going and do what he had planned, now the urgency of caring for the person he has met is a priority.

We also live our lives under the pressure of a thousand and one urgencies: we must finish this or that personal or professional project, we have to arrive on time for a meeting, or finish some accounts, or schedule a weekend outing, or do the shopping, or answer several emails that accumulate in our tray, or to return messages and phone calls...

And we too, like the three characters in the story, suddenly encounter badly injured people fallen in the ditches of our itineraries: brothers and sisters who are going through a personal crisis, who are sick, people hit by poverty and injustice, by anguish or depression, those who feel abandoned.

And then we must ask ourselves what is more urgent: to accomplish what we were planning to do with our day—or to try to do whatever we can to alleviate the pain of those we have encountered.

Often, an honest and compassionate look at the suffering of others puts our urgencies into perspective, showing us their exact measure. It is not that we suddenly discover that they were insignificant or imaginary. What we discover, in the face of other people’s misfortune, is they can wait. Maybe they were not that serious.

The Good Samaritan, with his ability to change his plans and pay immediate attention to the wounded man, shows us the path of mental flexibility, which is a condition for and prelude to mercy. In other words: with his decision to postpone his objectives to assist the stranger, the Samaritan teaches us that rigidity and inflexibility are often an impediment for charity and tenderness to flourish in the world. Other people’s crisis cannot be programmed: they arise unexpectedly, when we least expect them, like a man beaten on the side of our road. We will only be able to properly respond to these crisis if we are willing to postpone, over and over again, our emergencies.

In the coming weeks and months, we will be publishing short entries on this blog commenting, one by one, the Beatitudes of the Gospel of Matthew. We will do it without any attempt of erudition or academic scholarship—simply reacting carefully to what Jesus proposes, trying to apply it to our daily lives.

Preface

The Beatitudes from the Gospel of Matthew (Mt 5:1-12) are a fundamental text of the Christian faith, as well as one of the most beautiful pages of the New Testament. In them, Jesus masterfully summarizes his lifestyle, the lifestyle that he invites his followers to put into practice.

The first great virtue and merit of the Beatitudes is that, in them, Jesus avoids moral or moralistic language, and does not speak of the duty of his followers, of what they are obliged to carry out to be considered upright people. He does not prohibit anything either (in the line of the ten commandments of the Old Testament). The use of mandates and prohibitions would have turned the Beatitudes into a legalistic text, a new decalogue: perhaps useful and very wise, but not necessarily attractive or exciting. Instead of opting for the language of the law, Jesus describes his lifestyle, emphasizing what it ultimately is: a path to happiness. Happy are those who do what I am saying, he affirms. Happy. By framing his teaching in the context of joy, Jesus touches an intimate chord in everyone who listens to him. Because, who doesn’t want to be happy? Assuring that what he proposes is a journey towards joy, Jesus reaches every human being, of any age and culture, by appealing to one of the most universal desires that exist.

What then happens, of course, is that when we start reading, we find out that this path towards happiness is very paradoxical. We immediately realize that it is a surprising, daring program, far removed from the conventional formulas that we would instinctively think of if we were asked how to attain joy. Jesus’ proposal constitutes an alternative path to the one we usually imagine, from our categories and with our imagination, when we meditate on what is required to obtain happiness. This paradoxical character of Jesus’ proposal is already evident in the first beatitude.

"Happy are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven"

This is a statement that, if it is misunderstood, can lead to a dangerous demagogy: someone could use this first beatitude to praise and applaud material poverty, and could end up saying that poverty helps us become better people, and that to go hungry makes a person happy—something that any hungry person would deny without the slightest hesitation. No, Jesus (who, in line with all the Old Testament prophets, denounced economic inequality and the abuse of the poor by the wealthy and powerful) is not praising material poverty (because there is nothing praiseworthy in it).

What Jesus says, when he states that the poor in spirit will be happy, is, to begin with, that the first condition to obtain true joy is to acknowledge one’s need of other people: to be poor in one’s heart means to recognize that I need all that others, and God, give me. Thus, this first beatitude is fundamentally a serious warning against self-sufficiency. The arrogance of those who think that they are rich, in the sense that they do not need anything from anyone, is a sure path to bitterness, due to the simple fact that it is a lie: we all need others, and the sooner we recognize it, the better.

«For theirs is the kingdom of heaven.» Absolutely: only people who are aware of their fragility, their vulnerability, of needing the support, warmth, tenderness, consolation, company and friendship of others, will be able to live in the kingdom of God, the «place» where the values of the Gospel are to be found. The arrogant and self-important, the narcissist unable to recognize that other people can teach him something useful, those who see other people as a burden and not as richness, will not know how to live in a kingdom that is founded on fraternity.

In addition to this, the first beatitude has, indeed, an economic dimension. Because it is only logical to think that the poor in spirit are also those who have made a choice for a sober lifestyle. They have understood that, in this world, true wealth is to be found in others, and in the friendships that one can forge with them through life. Therefore, they have relativized the importance of all material treasures. They have understood that it is possible to live with less; they have grasped the danger of idolizing money. In consequence, they practice a healthy austerity, the responsible austerity of those who understand that the world’s resources are limited, and that, in our global village, the luxury of a few is paid with the misery of many.

Youth from La Resurrección Parish in Bogotá planting a tree near their church

The readings for the Sundays of Advent, especially those from the prophet Isaiah, underscore the importance of dreaming. They remind us that the ability to imagine a better future, a tomorrow in which today's problems are left behind, is essential. Isaiah dreams, and he dreams big; he dreams without limits. He dreams that one day, swords will be forged into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks, and that no one will train for war anymore. He dreams of a world without violence in which the strong will no longer destroy the weak, in which wolf and lamb, leopard and kid, lion and calf will live together without attacking each other. He dreams of a blossoming desert, where the blind will regain their sight, the deaf will hear, and the lame will leap like deer. Someone, without a doubt, could brand Isaiah as naive, crazy, deluded, and reproach him for living in an unreal world. He would surely reply that the only fools are those who do not dream. And that it is always better to hope for too much than to lock oneself in the resignation of those who assume that the problems of the present have no solution.

The prophets dream. Jesus also dreams. In his case, in a kingdom of brotherhood and justice (the kingdom of God is Jesus’ big dream), a kingdom of free people, of new men and women, in which even the smallest will be greater than John the Baptist (and «among those born of women there has been none greater than John the Baptist»).

Advent reminds us that if we don’t have dreams left, we don’t have anything.

And it is good to remember that everything (that is, everything good) starts with a dream. A family, a friendship, a project, a community... it all starts with someone entertaining an idea (which at the time may seem crazy) and telling themselves that it is worth working to make it a reality. «The struggle will be long. Let’s start right now» used to say Camilo Torres. And to start is to start dreaming. Many good things that today we take for granted and consider very normal, one day they were not. Furthermore, for the majority they were chimeras. Today they are a reality because someone dared to dream about them, and dared to think that they were possible. Someone, one day, imagined a world without slaves. Or a world without dictators, in which every four years the people would vote for their rulers. Someone dreamed of a world in which women had the same rights as men. A world where workers had a humane working day and a decent wage. A world in which the color of our skin no longer mattered.

There is still a long way to go («the struggle will be long...»). Yet, the fact that today millions of people live in countries without slavery, with democracy, in which women and workers can claim their rights and in which racism is condemned, is because someone, one day, dreamed of these achievements.

Advent is a time for those who stopped dreaming to do so again, and a time for us to consider which deserts in our lives should be flourish again.

One of the messages of this time of preparation for Christmas is, without a doubt, that we should not be afraid of dreaming in a better future. And if then someone accuses us of being dreamers, in the negative sense that we sometimes give to the term, let us remember that in reality the only fool is the one who no longer dreams.

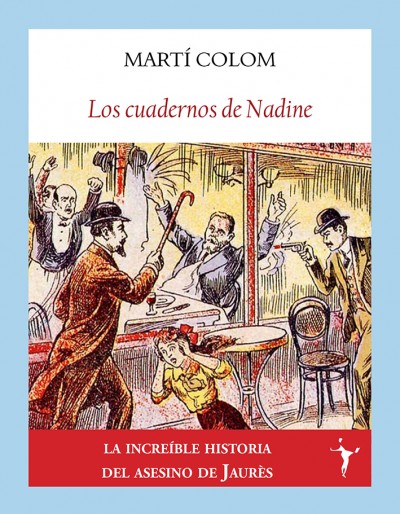

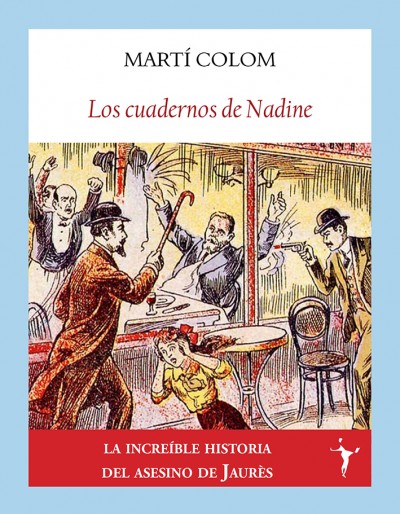

This September, Funambulista, a printing house from Madrid (Spain), has published the novel “Los cuadernos de Nadine” (“Nadine's notebooks”), by Martí Colom, a member of the Community of Saint Paul and a regular contributor to this blog.

The novel (published with the quality and care typical of books by Funambulista) opens with the story of the last days of Jean Jaurès, the leader of the French socialists who vehemently opposed the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914. Jaurès, knowing that the conflict would be a catastrophe in which the workers and the poorest in society had nothing to gain, was convinced until the last moment that it was possible to avoid the war, and he wore himself out orchestrating a political and public campaign against the conflict. As it progresses, the story focuses on the complex and tortured life of Raoul Villain, the man who murdered Jaurès, and on the contradictions faced by Nadine Ledoux, the young woman who loves Villain and becomes the true protagonist of the story, forced to decide what to do when the world she lives in falls apart.

“Los cuadernos de Nadine” is a fast-paced novel that, in addition to telling the unlikely (but true) story of Raoul Villain, confronts the readers with their own attitude towards violence and failure. Is it possible, ultimately, to remake one's own life when the certainties in which we had always trusted fall apart?

https://funambulista.net/libros/los-cuadernos-de-nadine/

This month—on the 19th—we celebrated the Feast of Corpus Christi, the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, and to illustrate the solemnity at Mass we read Luke’s account of the multiplication of the loaves and fishes (Lk 9:11-17). In this passage, two different ways of dealing with life’s challenges are immediately discernible.

On the one hand, faced with the pressing problem of the lack of food for the crowd that stands in front of them, there is the «solution» (let’s call it that) proposed by the disciples: that each one may look for what he needs. «Dismiss the crowd so that they can go into the villages and farms and find themselves bread». It is the law of the jungle: every man for himself.

And, on the other hand, there is the option that Jesus proposes: let us all stay here, together, and, united, let’s see what we can do about the problem we face. This, one could say, is the Eucharistic (that is, communitarian) way of life.

In the way of dealing with things of the disciples, no one takes responsibility for the well-being of the brother. Jesus, on the other hand, synthesizes his proposal precisely with the invitation (or mandate), that the disciples be the ones who start working to solve the needs of the crowd: «Give them something to eat yourselves» (Lk 9:13). And this becomes, then, the key phrase of the story. «Give them something to eat yourselves» is an order from Jesus that resounds throughout History, as an inescapable call to the ears and conscience of all those who, at times, would like to inhibit ourselves, shrug our shoulders, say that the needs of others are not our problem and to opt, with the disciples, for the law of the jungle, every man for himself.

In each celebration of the Eucharist we remember and emphasize that we come to receive communion as members of a community. In other words, we partake of the body of Christ (present in the consecrated host) in order to continue being the body of Christ (as Church, people, family), as Saint Paul said: «You are the body of Christ» (1 Cor. 12:27).

In this sense, it is obvious that there would be no greater contradiction than an intimate, privatized and individualistic experience of the Eucharist. It is beautiful that we experience the reception of the consecrated form as a moment of deep closeness with Jesus: but this should never become an excuse to then distance ourselves from others, under the pretext that «I am at peace with the Lord. Thus, I do not need anyone else». We receive communion, and in the act of receiving communion we feel the closeness of the Lord, yes: but the logical fruit of this closeness with the one who said «Give them something to eat yourselves» should be, time and time again, that then those of us who have received communion want to get closer and commit ourselves more with each other, and especially with those who are hungry. Because (we insist) we receive the body of Christ as members of the Body of Christ.

And what makes us be the Body of Christ, or the Church, or a people or a family? A baptism certificate? A passport, a flag? A surname, some genes? No, but rather what Luke’s text reveals: the ability to assume responsibility for one another.

A group of people where some take responsibility for the welfare of others is a community. On the contrary, one in which everyone goes their own way (regardless of whether they share nationality, or last name, or affiliation to the same church) will never be a true community.

Let us listen, with renewed ears, to the explicit words of Jesus: «Give them something to eat yourselves». In the capacity that we demonstrate to respond to this invitation hangs our very identity as members of the Church, as brothers and sisters, one with the other, forming the body of Christ.

Members of a youth group from La Resurrección Parish in Bogotá (Colombia),

after helping paint the house of a vulnerable family of their neighborhood during Holy Week, 2022.

The Beatitudes are one of the most beautiful pages of the Gospel. Brother Roger Schutz, founder of the ecumenical community of Taizé, in France, said that—together with the Our Father—we should consider them as the fundamental text of the Christian life. And we have two versions of the Beatitudes: those by Matthew (Mt 5:1-12), which are perhaps better known (the first that come to mind), and those by Luke (Lk 6:20- 26). We would like to focus on the latter, and on the differences with the Beatitudes of Matthew, and on the message that is hidden precisely in these differences.

To begin with, in Luke Jesus does not announce the Beatitudes from a mountain, as it happens in Matthew, but on a plain. This geographical location is significant: while Matthew wants to underline that the Master speaks from on high (the removed place where one arrives to meet God), in Luke Jesus pronounces the Beatitudes on the valley, the space where people live.

In Matthew, the first beatitude reads: «Blessed are the poor in spirit.» On the other hand, in Luke it will be «Blessed are the poor»: just the poor, the material poor. A few verses further down, Matthew will say that blessed are «those who hunger and thirst for righteousness.» Luke’s second beatitude will simply be «Blessed are the hungry.» Not those who hunger for righteousness, but those who hunger for bread.

Somehow, while Matthew underlines Jesus’ invitation to be people who have chosen to live simply and in austerity, who have become poor as a result of a personal decision, and who have a deep inner desire for justice in the world, Luke’s message is more social, less spiritual: blessed are the poor and the hungry, because God is on their side.

Both versions of the Beatitudes are important. Matthew’s, emphasizing interiority and our ultimate options, those we cultivate when we seek spaces of solitude and find God on the mountains of peace— and Luke’s version, emphasizing our social commitment, the one we assume in the valleys of the world, confronted with the reality of the material poverty suffered by so many (material poverty which is scandalous in a world where we could all live comfortably if wealth were not so poorly distributed).

In Luke the message is, with all clarity and energy, that God takes the side of the victims of this world: happy will be the poor, the hungry, those who cry, because they are God’s beloved.

And this implies, of course, a question: What about us? Do we always side with the victims, the oppressed and the humiliated, or, perhaps, in order not to create problems for ourselves, are we among those who remain silent in the face of injustice, or do we even join the group of those who only seek their own good?

In this same social line, the Beatitudes of Luke have something that those of Matthew do not have: they are accompanied by some warnings. «Woe to you!» To whom are these warnings addressed? To the rich, those who are satiated, those who laugh, those of whom everyone speaks well.

And what's wrong with laughing, or being satiated, or being talked about well? These are the attitudes that describe people who are complacent with their environment, who agree the state of the world as it is, and who therefore live carefree. Woe to those, in short, who adapt too much to their environment! And that is a very serious warning: in this world of ours, so pierced by injustice, feeling too comfortable (perhaps because things are already going well for me) is an act of evident selfishness.

One looks around and sees so much injustice, so much oppression, so many people working so hard for so little, and others working so little for so much, and so much abuse, so much violence, so much cruelty, so much indifference—that it is logical to conclude that no one should ever say, «Everything is great!» A Christian is a person who is aware that the world is not great, and therefore does not uncritically accommodate himself to it: on the contrary, he protests and works to build a more just society.

Let us make the Beatitudes our own: those of Matthew, more spiritual, that invite us to examine our ultimate, intimate choices about the kind of person we want to be. And Luke’s, more social, that encourage us to develop a greater social commitment with the poor and those who suffer.

Happy Easter! Jesus has risen!

This great feast, center of the liturgical year and of our entire Christian faith, invites us to seek Jesus among the living. Let us stop looking for him among the dead, in everything that destroys and oppresses, where there can be no green shoots of hope!

Jesus, alive among the living, is not to be found in violence, which only generates more violence, and blindness, and death, discouragement, and sadness.

Jesus, living among the living, is not to be found in contempt, in situations where some look with disdain at others because of their race, their social status, their gender, their orientation, their past...

Jesus, alive among the living, is not to be found in those contexts of privilege and inequality where a few enjoy the goods that belong to all.

Jesus, alive among the living, is not to be found in the indifference that kills, in the indifference because of which the pain of those living on the margins of society becomes invisible, as if it did not exist… as if they did not exist!

We must look for Jesus, alive among us, in the gestures of peace and reconciliation of those who have understood that war, brute force, insult and slander are never the way.

We must look for Jesus, alive among us, in those who welcome everyone with open arms, whoever they are, wherever they live, however they love...

We must look for Jesus, alive among us, in the efforts of so many people to build groups and communities of the Gospel, where fraternity is not an empty word, where synodality and walking together is the formula to learn to listen to each other and value the richness of plurality.

We must look for Jesus, alive among us, in the sensitive hearts that are moved, over and over again, with the pain of the poorest, the Father's favorites.

The followers of Jesus, in short, are people who strive, always, and sometimes with a stubbornness bordering on obstinacy, to look for signs of new life in the world, aware that the strength of the Risen One always ends up making itself present wherever there are human beings open to the life-giving, liberating and renewing Spirit of God, who raised Jesus from the tomb.

Let's celebrate Easter by finding Jesus… Alive in our midst!

Our relationship with time can be oppressive or liberating. It all depends on the eyes and expectations with which we look at the past, the present and the future.

We live inserted in time: to be a person is to exist in history, to grow through the stages marked by the years. And it is healthy to ask ourselves what kind of relationship we have with time: with the past, the present and the future. These three dimensions of existence can become oppressive tyrannies or beautiful gifts, depending on how we relate to them.

The past can be a tyranny, a heavy rock that crushes us and prevents us from growing, when it is filled with suffering—when we are unable to let go and detach our today and our tomorrow from a yesterday cluttered with painful moments. It is common for people with a dark and distressing history to live subdued by the memory of the wounds they suffered: they feel defined, handcuffed, and subjugated by their past; a past they would rather forget and, yet, remains alive in their memories.

In other cases, the past can be a tyranny when the opposite happens and, instead of being a source of painful memories, it is full of joy. Remembering the happiness they savored, some people can chain themselves to their golden past, and fall into a sickly nostalgia that will prevent them from enjoying the present or from having exciting dreams about the future. They live trying to obsessively repeat, over and over again, what they already experienced: «Since my best years are behind me, they tell themselves, I must labor to reproduce them». This nostalgic and futile concern stops us, frustrates us and prevents us from seeing the possibilities offered by the present and the future.

Other people live immersed in the tyranny of the present, when they insist on turning today into the best day of their lives. Today is when I must experience everything, they say: yesterday doesn’t count, because it is gone. And tomorrow is uncertain; therefore, the only real thing is this moment, it is now, and now is when I must fulfill myself to the fullest. Instead of conceiving the present as one more moment between what has already taken place and what is yet to come, some may conceive it as the urgent scenario of a fullness that cannot be postponed. And it is true that yesterday is already gone, and that tomorrow is uncertain, but living without taking them into account, magnifying and exalting the present as the only thing that matters, impoverishes our perspective. The tyranny of the present (the self-imposition of thinking that today I must achieve all my dreams) subjects us to the immediacy of this precise moment, lacking both the wisdom offered by meditation on everything that has already happened to us and the hope that invites us to cultivate what is yet to come. The obligation of having a perfect, wonderful and stimulating present is a pipe dream (and, as such, a source of frustration). There will be times when our now will be beautiful and pleasant, and there will be disappointing, uncomfortable or painful «nows». Today cannot be constantly my best day.

The future can also be a tyranny when the years go by and we keep accumulating experiences of all kinds and, yet we persist in believing that the best is yet to come. We disdain past and present betting all our happiness on a tomorrow that we anticipate undoubtedly bright and shiny. What if it is not so? What if the most beautiful or stimulating or profound thing in your life does not lie in the future, but in the past? We should not stop dreaming, we should not give up having projects; but we surely should be grateful for what we have already experienced. Then, we can reject the tyranny of the future, the obligation to live always projecting ourselves towards what is to come. It is healthy to reject the subtle deception of blindly believing that what is important, significant, and relevant in our journey is yet to happen. It could be so, or not: maybe that trip we made a few years ago, or that extraordinary book I finished yesterday, or that conversation, or that friendship, or this moment of deep intimacy with someone or this hug already lived will be the most beautiful gift that your biography will give you. The constant expectation regarding what is to come can prevent us from calmly enjoying the riches of the present and valuing the joys of the past in their proper measure.

Our relationship with time, in short, can be painful: it is very possible to fall under the tyranny of the past, present or future when we conceive one of these dimensions as the only one that matters (forgetting about the others), and, in addition, we ask from it something that it cannot give us.

Past, present and future, on the other hand, can be an inexhaustible source of joy and a wonderful gift when we conceive them as an interconnected whole (the past is a dimension of the present, according to William Faulkner) and when we ask of each one of them what they can really offers to us.

The past is a gift when we manage to accept that everything we have experienced (from the most beautiful to the saddest) is a school of learning, including the conflicts and disappointments that one day made us suffer. And the years we leave behind are a gift when we manage to accept these sufferings from yesterday as part of our biography... a part of our biography that, although we would rather not have experienced, we can now integrate into our understanding of life, aware that everything (from the happiest to the most disastrous) contains valid teachings. The past is also a gift when we understand that, although the beauty and joy that we once lived should not become reasons for useless nostalgia, they can be a source of satisfaction, and it is healthy to preserve as treasures the memories of so many people who one day accompanied us, of so many gratifying moments that we can contemplate with a deep sense of gratitude. The past is a gift when we understand it as the land where our identity has matured, the workshop where the best of us has been forged, the history full of teachings that equips us to live the present and the future with more wisdom, without repeating mistakes, with serenity. Instead of looking at the past as that time to which we are always forced to return (either because then we suffer wounds that still hurt us, or because we want to recover the good things it gave us), it is possible to live with gratefulness for the experiences accumulated: without denying them their importance, and—at the same time— without exaggerating their role. The past is indeed the architect of our identity, but nothing prevents us from letting go of its most toxic aspects or freeing ourselves from a nostalgia that prevents us from giving ourselves enthusiastically to the present and the future.

The present is a gift when—without expecting that each moment be the most beautiful, the happiest or the richest that we have ever lived—we understand it as the arena in which we can become acutely aware of being alive, and when we see it as the moment in which we can also become aware of the world around us. The present is also the space of creativity where we can carry out something new; the territory where, without forgetting the past, we can go beyond old routines and perhaps reach some level of maturity hitherto unknown. The present is the arena where we can be fully free, the now in which it is possible to put everything we have lived at the service of a renewed effort to fully tune in with our environment, with others, with our interiority... and with God. Because, from a faith-filled standpoint, the present is the moment in which God’s today is manifested, the today that invites us to understand what we are experiencing right now as the stage in which the Father shows us his love, the “today” that Jesus announced in the synagogue of Nazareth after reading the scroll of the prophet Isaiah: «Today this passage that you have heard has been fulfilled» (Lk 4:21).

And the future is a gift when, while being aware of its fragility and the uncertainties that surround it, we see it as the horizon where perhaps the possibility of further growth will still be given to us. As well as the possibility of finding out more about the meaning of our lives in this world, and to discover new lessons about life, about others or about oneself. The future is the territory of hope, it is the area from which we can expect new beginnings, new encounters, and new projects. The future is the place where we can foresee ourselves as better people, free from the miseries that crippled us yesterday and that perhaps still dwarf us today. The future invites us to dream.

Our relationship with time can be oppressive or liberating. It all depends on the eyes and expectations with which we look at the past, the present and the future.

There is a tragic and bitter irony in the fact that a new war breaks out in the heart of Europe (something that to many of us seemed an impossibility) just a few days after in all our churches we heard—last Sunday—the radical proposal of Jesus to end violence.

The Gospel reading for the seventh Sunday in ordinary time, which we celebrated just four days ago, was the passage from the sixth chapter of Luke in which, precisely, Jesus invites us to break the cycle of violence (Lk 6:27-38). By asking us to love the enemy and turn the other cheek, Jesus is not asking us to be weak, timid, or humiliated. This is not the purpose of these words. What Jesus proposes, however arduous it may be to put into practice, is the only possible path to a solid and lasting peace. It is the path of non-violence that disarms, that deactivates the logic of war. It is not surrender or weakness: in fact, you have to be very brave to turn the other cheek. Only those who have understood that war is the worst of evils, and that it must be stopped at all costs, will be able to do so.

This appalling «failure of language» that is war (as Mark Twain defined it) is striking Ukraine today. The image of tanks and planes crossing a European border and invading a neighboring and sovereign nation is overwhelming. The temptation would be to believe that humanity is not advancing. That we always go back. That when we had understood that peace is sacred and that nothing justifies violence, we forget it again.

And, suddenly, a different story: the same day that the Russian army invades the neighboring nation, demonstrations against the war take place in more than fifty Russian cities. More than 1,500 people are arrested for participating in these marches.

They are brave. They raise their voices against the primitive and horrifying use of force ordered by their government.

Perhaps, after all, the words of Jesus did not fall on deaf ears. In the long run, only they, only the unwavering decision to stop violence by loving the enemy and turning the other cheek, will guarantee peace.

Today we celebrate the great feast of the birth of Jesus, the feast that, in a way, changes everything: the arrival of that child, and the good news that he announced, marked a turning point in the history of the human family. For believers, the feast of the incarnation means a profound transformation of the very idea of God: the haughty and distant God in whom we had believed, sometimes indifferent, other vengeful, always a judge, now comes to us in this poor and trembling baby, guarded only by his parents, humble and simple people, and an ox, and a cow. And that new identity of God, made one among us, is, indeed, an immense reason for joy.

One of the most endearing Christmas texts is the one we read, in preparation for today’s feast, on the fourth Sunday of Advent: the visitation of Mary, pregnant with Jesus, to Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist. In this passage, Luke underlines precisely the joy that the presence of the child Jesus (in his mother’s womb) provokes around him: both Elizabeth and Mary herself are filled with joy, and the child John «leaps for joy» in Isabel’s belly.

Do we leap for joy when we feel close the presence of God?

It is a question worth asking. Because it is intriguing to observe that, often, the reaction that a closeness to the sacred provokes in us is not the reaction of John the Baptist—not one of joy, but of fear. Or guilt. Or both at the same time. Can we imagine Elizabeth saying to Mary, «When your greeting reached my ears, the child began to tremble with fear in my womb»? Or, «When your greeting reached my ears, the creature began to beat its chest, saying “through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault”»? And yet, that seems to be, sometimes, our response, when we feel the proximity of God.

These are perhaps understandable reactions. The divine is immeasurable: confronted with it, we become aware of our smallness, and, since we have been taught since childhood that God is a severe judge, then his closeness terrifies us. And our guilt seems more obvious to us, in his presence: this is what happened to Peter, that when he understood who Jesus was, and then exclaimed «Leave me, Lord, I am a sinful man» (Lk 5: 8).

And yet, these are reactions that respond to a pre-Christian idea of God—reactions that do not consider the Gospel. The fear and trembling that the sacred causes us is rooted in the experience of cultures that associated God with the terrible phenomena of nature, and that developed the idea of a God who, in any case, had to be appeased with our sacrifices. And all that has nothing to do with Jesus and his message; indeed, that is precisely what Jesus came to dismantle, with his good news that God is a merciful father, who loves us beyond comprehension.

To fully understand Christmas is to understand that the God in whom we, Christians, believe should always be, for us, a source of joy. Because Christmas means that God is not a judge, but a brother, who does not come to condemn us, but to walk with us, who does not look at us with disdain, but with tenderness, a God that we should not worry about appeasing, whom we should rather thank for all his goodness.

The question that we should then ask ourselves is whether with our behavior and attitudes we help to communicate that the closeness of God is comfort, and reason for happiness, or not. There is no doubt that sometimes, with our severity, with our rigidity and harshness, even with our bitterness, what we do is perpetuate the idea (this pre-Christian idea which contradicts the Gospels) that, before God, the most logical attitude is to be scared. When, in fact, the most natural thing would be to react like John the Baptist: leaping for joy.

A very blessed and merry Christmas to everyone!

Three weekends ago, at the Eucharist corresponding to the Thirtieth Sunday in ordinary time (cycle B), we read the passage from the Gospel of Mark that tells us about the healing of the blind Bartimaeus (Mk 10:46-52). Here we do not wish to develop an exhaustive interpretation of the episode. Rather, we would like to focus on a very specific detail: when some of those who walk with Jesus encourage the blind beggar to get up, because the teacher is calling him, he, the text tells us, «Threw off his cloak, jumped to his feet and approached Jesus». We all know what happens next: Jesus asks him what is that he wants, Bartimaeus replies that he wishes to see again, Jesus tells him «Go, your faith has healed you», and Bartimaeus regains his sight and begins to follow Jesus on the road (thus completing his conversion, since at the beginning of the story he was sitting «by the roadside», where—if we remember the parable of the Sower—is where the first seed fell, and bear fruit).

The detail we want to underline is the precision offered by Mark that we have highlighted in italics: before getting up to go to meet Jesus, the blind man dropped his cloak. What does this cloak represent?

Most likely, in the evangelist’s mind, the cloak symbolizes Bartimaeus’ old identity (the one that kept him blind, having placed him on the roadside) which he had to abandon in order to follow Jesus with complete freedom. Or perhaps Mark wants us to think of the cloak that the prophet Elijah threw over Elisha (1 kings 19:19), representing the authority of the master, who passed on to his disciple: Bartimaeus’ gesture, to get rid of the cloak, would then signify his relinquishing of a position of power to which he, until then, had been clinging.

However, we would like to attempt another interpretation. Bartimaeus is a beggar, a homeless, and to go to meet Jesus he gets rid of his only possession. Indeed, the cloak was all that he to protect himself from the cold, the rain, the bad weather. Seen like that, Bartimaeus’ cloak appears to us as the symbol of those minimal and precarious possessions that the poor own. It represents the rudimentary well-being that our society grants to the poorest—in order to keep them quiet.

Our capitalist world, so much oriented towards the constant accumulation of wealth, allows the poorest to have what one could call a mirage of patrimony. If, in our increasingly unequal societies, vast numbers of people owned absolutely nothing, and were literally starving, there would be a social outbreak and a revolution every day. To avoid this, the economic system in which we are immersed tolerates that the most unfortunate have something: in the poorest and most vulnerable homes in the most peripheral neighborhoods of a large Latin American city such as Bogotá or Mexico (for example) there is a television , even if he it is an old one; and people have a cell phone, even if the screen is scratched, or half broken, or the device is discharging every ten minutes because the battery is already quite exhausted; and there is a refrigerator, and in the refrigerator there is some food, even if it is of poor quality, and not very healthy. This rickety television, this phone with the screen half broken, and this unhealthy canned food are the cloak with which millions of Bartimaeaus continue to protect themselves from the elements today. Crumbs that the unfair system allows them to enjoy, as long as, in return, they remain silent and docile.

The gesture of the Bartimaeus, throwing off his cloak, reveals the awakened person, the one who opens his eyes and realizes the infinitely fuller life that he could enjoy next to Jesus, and realizes the crumbs with which some people have tried to numb his conscience. Once he walks by Jesus, with his sight recovered, he will have acquired a much deeper sense of his own worth. He will have understood that faith demands justice. He will have understood that, from the eyes of God, we all have the right to a real well-being, not just an apparent one. Bartimaeus, in short, casts the mantle aside because he is now aware of his own dignity.

On October 9 and 10, Pope Francis will begin, in Rome, the preparatory stage of the XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops. A week later, on October 17, all the dioceses of the world will inaugurate the consultation and preparation phase, at the local level, of this synod of the Church, which will culminate with the meeting, in Rome in October 2023, of the participants at the actual synod gathering, who will approve a final document. The theme proposed for this very important ecclesial event is For a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation and Mission. In other words, the issue on which we are invited to reflect is precisely synodality, the way of being, of operating and of moving forward of the Church as an authentic community of brothers and sisters, where all voices are heard, where no one is left lagging behind, where we all feel like companions on the road, advancing at once (which is exactly what the etymology of the word synod means, made up of the Greek prefix sin —reunion, joint action— and the noun odos —way, path). To practice synodality is to walk together.

Francis proposes that the Church, taking up the teachings of the Second Vatican Council (which stressed that the ecclesial community is, above all, a family, the People of God, where everyone counts and everyone has a mission), may assume its communal identity and renew her commitment to be, more and more, an articulated body that advances without discarding or marginalizing anyone, a body in which everyone, from the bishops to the most recent baptized believers, feel and are true companions on the journey.

This commitment, and this synod, are necessary. Because, despite the extraordinary advances made since the Council, when we look at our parishes, communities and ecclesial movements, we realize that we still have a lot of work to do. In how many parishes must everything still go through the pastor (from the most vital to the most trivial decisions), who reigns over his parishioners with a style more typical of a feudal lord than a shepherd? In how many religious congregations and dioceses is authority still exercised without the slightest dialogue between those who ordain and those who obey? In how many movements and institutions that call themselves Christian are the leaders and founders treated with an unhealthy cult of their personalities, which stifles any constructive criticism of their leadership before it can even be formulated? How many groups —starting, of course, with women, who, if I am not mistaken, make up half of humanity— still participate in the life of the Church in a peripheral and marginal way, without access to many areas, roles or functions?

We repeat beautiful sentences from the Council that emphasize the participation of all the baptized in the life of the Church, but in practice we are still a strongly hierarchical, often authoritarian structure, in which consensus matters little and in which some voices have a disproportionate weight, to the detriment of others.

In this sense, the next synod is a reason for hope. Let us pray, from now on, for its success. So that the Spirit, who, like the wind, «blows wherever it pleases» (Jn 3: 8) guide us along paths of authentic conversion in favor of synodality, this desire (so close to the heart of the Gospel) to leave no one behind, to listen to all voices and to count on everyone, especially on those that our society—and also the Church—tends to ignore and marginalize.

Can the Christian faith ever become a private matter, limited to the domain of the individual conscience?

The Gospel could be compared to music written on a piece of paper. What is, a musical score? It is a sheet of paper with signs on it, signs intended to become music. A staff full of notes that no one would ever play or sing, and that never, not once, would become a melody, would be a contradiction, an absurdity. Likewise, the gospels were written to be lived out. They are a collection of texts that want to become life, and it would be a complete contradiction for us to look at them from a distance, to perhaps study them, to examine them carefully (a useful thing, to be sure), if then we did nothing to put them into practice. What we would like to emphasize here is that, if a musical score exists to become a melody, the gospels exist to become community life and to shape the world. Indeed, this «putting the Gospel into practice» necessarily entails an experience of community, of people who—either as a family of blood, or as a family of faith, or as a group of friends, or as a parish team, or as an institute of consecrated life—, together, try to embody, in their own time and circumstances, what they learn in the gospels. And, together, then, they try to better the world they live in, making it more livable for everyone.

Today, in many cultural contexts, the idea that faith should be something strictly private, which would only affect the personal consciousness of individual believers, is gaining weight. I recently read a somewhat unfortunate article by a journalist (with whom, on the other hand, I usually agree), in which the author stated precisely that «no one should mock any religion, because, as long as it limits itself to the personal domain, what is the problem?» This is the issue, the crux of the matter. If the Gospel is to be enclosed into the personal domain, if it does not become fraternal life and action for social transformation, if it becomes something strictly private, then it will cease to sound. If we turn the Gospel into something private, we silence it.